As the nation reels from violent protests that left one person dead and 19 others injured in Charlottesville, Virginia, a trial of Cliven Bundy’s armed supporters in Nevada is raising thorny issues around the threat of violence and its relationship to free speech. Defendants in the first of three Bunkerville trials, which wrapped up this week, have described their actions as being protected by the First and Second Amendments to the Constitution. But prosecutors say the trial is about men who used the threat of violence to defy law enforcement, and that the law does not protect people who intimidate, threaten or assault others.

During the six-week trial of Eric Parker, Scott Drexler, Steven Stewart and Ricky Lovelien, the prosecutors and defense team painted starkly different pictures of the events of April 12, 2014, when armed supporters of the recalcitrant rancher Cliven Bundy stopped the Bureau of Land Management from seizing cattle grazing illegally in southern Nevada. The defense characterized the Bunkerville standoff as a peaceful protest in which no one was hurt: Bundy supporters didn’t actually use the rifles they carried, but had them in case the BLM or National Park Service opened fire. Government prosecutors argued that even though defendants didn’t fire their weapons, they used the threat of violence to force federal officers to abandon their jobs that day.

This story originally appeared at High Country News and is reprinted with permission.

In fact, prosecutors said, the defendants have been part of self-styled militias that strategically used the threat of violence to thwart federal officers. Prosecutors described how defendants traveled in 2015 to Oregon and Montana to prevent federal authorities from accessing mining claims in those states. “The point is that these operations were done to show force to federal agencies… to make them stand down and stop what they are doing,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Nadia Ahmed said in closing statements this week.

The end of the trial has come just as national debate over similar issues has reached a new pitch. Dozens of far-right groups and hate groups have become emboldened since the election of President Donald Trump. These groups—which hold a vast diversity of beliefs but share many far-right values—have sponsored what they call “free speech” rallies across the country for months, often leading to violent clashes with counter-protesters. “We’re trying to show that folks can stand up for white people,” Jason Kessler, an organizer of the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, told a local radio station. “The political correctness has gotten way out of control, and the only way to fight back against it has been to stand up for our own interests.”

Last week the American Civil Liberties Union defended people’s right, even if they are racist, to gather in Charlottesville. Street brawls broke out, and a man allegedly drove a car into a crowd of counter-protesters, killing activist Heather Heyer. State and local officials across the country must now grapple with the conundrum of whether to revoke permits for more “free speech” rallies that threaten violence.

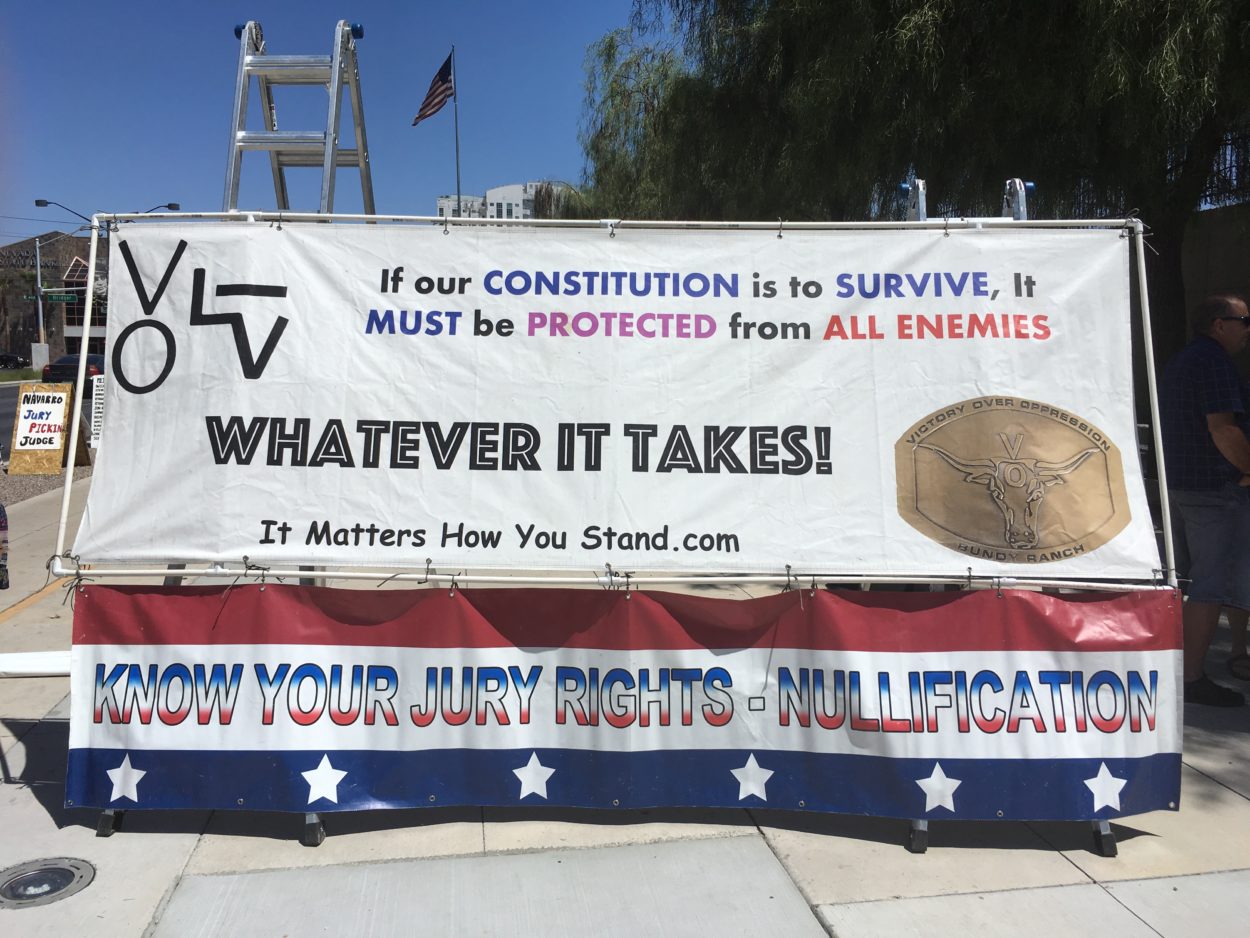

Meanwhile, at the courthouse in Las Vegas, Bundy supporters show no real desire to respect federal authority. Friends, family and other followers who have rallied outside the courthouse for months say that the judge has put unfair restrictions on the defendants’ case. U.S District Court Judge Gloria Navarro has in fact been stricter than she was in the previous trial, which ended in a hung jury for these four defendants. On Aug. 10, she kicked defendant Eric Parker off the witness stand because he would not keep his testimony within her court orders. Navarro had set limitations on testimony to exclude statements about what the defendants felt at the time of the standoff, which she deemed part of an irrelevant self-defense.

Bundy supporters have harshly criticized Navarro for months, sharing social media posts from outside the courthouse, saying she is biased and calling for her to be impeached. A New Mexico rancher who met Cliven Bundy decades ago and shares similar views on federal authority told me outside the courthouse this week that the judge, who is Latina, should be “strung up by that tree over there”—a comment recalling a period in U.S. history in which African Americans were lynched as a form of systemic oppression and terror.

The Bunkerville standoff was a rally against federal authority, not for white supremacy. Among the rancher’s supporters, the faceoff has become a symbol for standing for free speech. But for Bundy critics, it was a threat of violence.

Defendant Scott Drexler of Idaho testified in court this week that he traveled to Bunkerville in 2014, thinking he was attending a protest. “I guess the idea at the time was we were going to stand around with some signs,” Drexler said. “Did you bring a sign?” a prosecutor asked him. No, he said, though he brought an assault rifle and a pistol. To drive home her point, Ahmed played a video of Cliven Bundy’s son Ammon, shortly following the standoff, in which he said: “We did have militia and weapons, and that was important because (the federal officers) didn’t know whether or not we were going to fire on them.” Creating that uncertainty, the prosecutors argued, was a threat of violence, punishable by law. Whether this line of reasoning will hold remains to be seen. A verdict in the trial is expected as early as this week.

High Country News is a nonprofit news organization that covers the important issues that define the American West. Subscribe, get the enewsletter, and follow HCN on Facebook and Twitter.