A new report released this week found that pollution from oil and gas costs billions in health damages annually and contributes to early deaths as well as childhood asthma.

The study, which was published in the journal Environmental Research: Health, looked at data from 2016, before New Mexico saw surging levels of extraction. Corresponding author Jonathan Buonocore, an assistant professor at Boston University, said that the impacts are likely more severe now due to the increased production.

In 2016, the pollution from oil and gas worsened asthma in more than 410,000 instances and led to more than 2,000 new cases of childhood asthma and 7,500 excess deaths, according to the study.

The pollution caused $77 billion of health-related damages in 2016.

Buonocore said the study demonstrates that policies should target more than just methane emissions from the extractive industries.

Methane’s main impact when emitted is in its contribution to climate change, he said.

The study states that, when monetized, the air quality impacts to health exceeded the estimated monetized cost of the climate impact of methane emissions from the oil and gas sector by three times.

“A lot of folks exclusively pay attention to the methane emissions, forgetting that there’s more than just methane that’s being emitted from production,” Buonocore said.

Buonocore said the researchers started by gathering U.S. Environmental Protection Agency data on oil and gas emissions. They ran the emissions inventory data through an atmospheric program known as CMAQ, or community multiscale air quality monitoring. CMAQ is an open-source development project that the EPA created.

After running the data through at the 2016 levels, Buonocore said the researchers then zeroed out the emission data and ran it as if no pollution from oil and gas had occurred.

The researchers then used a health impact assessment platform to determine the monetary costs of the pollution as well as the health impacts.

Buonocore said this platform overlays the air pollution data with population baseline rates and uses existing epidemiology to determine how exposure impacts health.

“Once you get everything lined up and spaced, you can just run it through a mathematical formula and get health impacts,” he said.

When the study began, the 2016 data was the most recent set available.

He said the study shows that pollution from oil and gas has such a big impact on health that it should always be considered alongside the climate impacts.

The pollutants causing those deaths and health impacts include nitrogen oxide, fine particulate matter and ozone.

While the impacts were most pronounced in areas with oil and gas production, even places like Boston were impacted.

Buonocore said the closest oil and gas production sites to Boston, where he lives, are in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, parts of Maryland and a small area in New York.

The researchers found that Texas, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Oklahoma and Louisiana had the highest impacts, but even states with little oil or gas production like Illinois and New York ranked in the top ten.

Buonocore said that when population is taken into account, New Mexico’s number of deaths per million is really close to the number of deaths per million that occurred in Texas. Texas led the nation in the number of deaths related to the emissions from oil and gas.

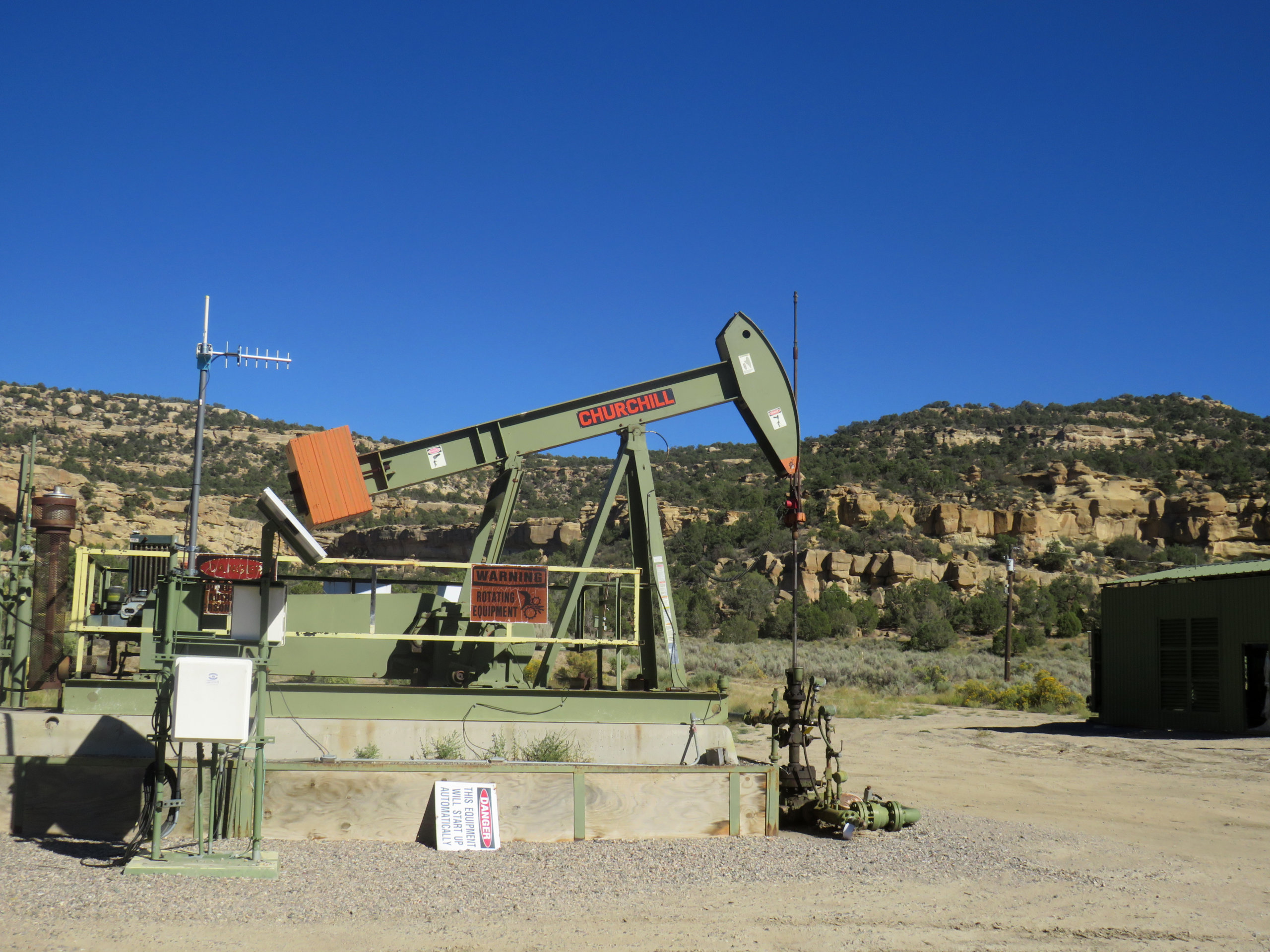

One thing that stood out to Buonocore was that the emissions profiles showed a large portion of the health impacts came from on-site fuel consumption including flaring and pumpjack engines.

Buonocore said that these impacts can be decreased through policies that curb all emissions from oil and gas, not just greenhouse gasses. That includes policies that prohibit routine venting and flaring.

In a press release, study co-author Ananya Roy, who is a senior health scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund, said the EPA should strengthen and finalize its proposed methane rules as quickly as possible.

“These proposed rules should build from leading state approaches in Colorado and New Mexico and go further to end pollution from the practice of routine flaring,” Roy said.

The study was funded by a grant from the Environmental Defense Fund, but Buonocore said the funding source does not change the results. He said the study has real science in it and went through a peer review process which checks the accuracy, methodology and results.

Buonocore said the type of information the researchers gathered during the process “could and should be used in designing energy policies.”