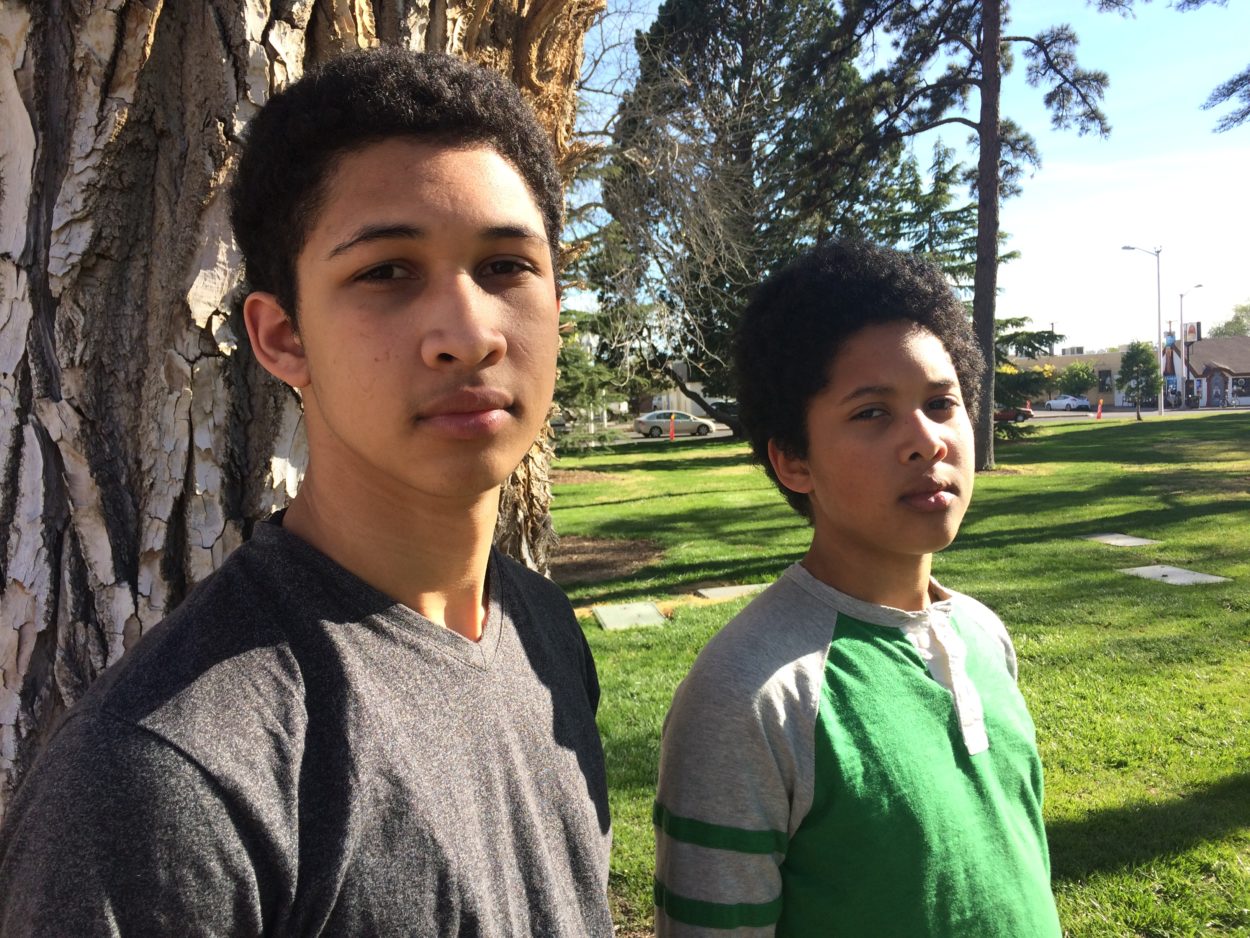

Two years ago, 21 children and teenagers sued the federal government, alleging that it had violated their constitutional rights to life, liberty and property by taking actions that cause climate change and increase its dangers. The young people, including Albuquerque-born Aji Piper, want the government to align carbon emissions reductions with what scientists say is necessary to avoid catastrophic and irreversible warming.

“Going to rallies is great, speaking up is great,” said 16-year old Piper of climate activism. “But we need to get our government in on this.”

The youth say that by not cutting greenhouse gas emissions, the government has failed to protect essential public trust resources like land, air and water for future generations. The suit is led by Our Children’s Trust, an Oregon-based nonprofit, which tried to stop intervention by the fossil fuel industry in the case.

But in 2016, a court allowed three industry trade groups to join as defendants. Together, the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufactures, the American Petroleum Institute and the National Association of Manufactures represent thousands of companies, including Koch Industries, ExxonMobil, BHP Billiton, BP and ConocoPhillips.

Working together, the government and industry tried to have the case dismissed. Those attempts were denied, including by District Court Judge Ann Aiken, who wrote in her order “[f]ederal courts too often have been cautious and overly deferential in the arena of environmental law, and the world has suffered for it.”

Neither the young plaintiffs, like Piper, nor the attorneys are messing around on the case.

Since November’s election, they have also named President Trump as a defendant and asked to depose Tillerson, former CEO of ExxonMobil who is now Secretary of State, a move the federal government is fighting. They’ve also requested the federal government and industry be prevented from destroying documents relevant to the case, including emails Tillerson sent about climate change from a pseudonym account while at ExxonMobil.

Related story: Orders from Trump, Zinke reverse nation’s climate and energy policy

The federal government has appealed that, saying it represents a hardship, said Piper.

The case is supposed to go to trial later this year. “If we won,” he said. “The government would have to start regulating fossil fuel emissions on a hard and fast basis.”

Piper and his brother, 12-year old Adonis Williams, are plaintiffs in a similar lawsuit against the state of Washington. That suit, which the state of Washington has fought, would require the state’s Department of Ecology to base its emissions reductions on the best available science.

Williams said he looks at his peers sometimes and wonders, “What are you doing with your life?” He said sometimes other kids ask him if he’ll win money if the lawsuit prevails and then lose interest in the conversation when he says it isn’t about money.

“I’m doing it so that my future is protected.”

The warming won’t stop

When it comes to the impacts of climate change on the southwestern United States, the case is clear.

The longer southwestern states wait to take action on climate change, the less water they’ll have, said Dr. Jonathan Overpeck. “And the change will be mostly irreversible on human time scales, for hundreds of years,” he said.

According to the New Mexico drought monitor, about half the state is still abnormally dry, but the map lacks the orange and red splotches of drought endemic to the map for years now.

But Overpeck cautions that the region’s 17-year long drought is not over.

“It’s still very real, and it’s exacerbated by record-high temperatures,” Overpeck said at the end of March to an auditorium of students, professors and others at the University of New Mexico. Drought in California and New Mexico are part of a bigger Southwest-wide drought: “California is just the most recent manifestation of that,” he said. “Since 1999, this drought has been moving around the Southwest.”

Overpeck directs the University of Arizona’s Institute of the Environment. He also worked on the fifth assessment report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2014 as one of the lead authors of the chapter on terrestrial and inland water systems.

Earlier this year, Overpeck and Colorado State University’s Brad Udall published a paper showing that warming has already reduced flow in the Colorado River, which supports 40 million people in seven states. The cities of Albuquerque and Santa Fe each receive water from the Colorado River system via the San Juan-Chama diversion.

They found that between 2000 and 2014, Colorado River flows were 19 percent below the 1906-1999 average.

With continued warming, the two estimated that declines will continue. By the mid-21st century, the Colorado River’s flows will be 20 to 55 percent lower.

And the warming won’t stop in the year 2100. “It keeps getting worse and worse and worse,” he said. “We don’t have analog for what’s happening now. But we know when we put CO2 into the atmosphere, it warms.” The biggest uncertainty, he said, is how much greenhouse gases humans will continue pumping into the atmosphere.

Related story: Vulnerable to climate change, New Mexicans understand its risks

Greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide trap heat within the Earth’s atmosphere. That understanding of the planet’s carbon cycle dates back more than a century, and the link between the burning of fossil fuels, the release of carbon and warming was noticed in the 1930s.

“Want to bet your house that it’s going going to be warmer in 30 years? That’s a good bet.” The trickier gamble, Overpeck said, will be guessing how much warmer it will be.

“Climate change is water change in the SW, and it’s all negative,” Overpeck wrote in an email to NM Political Report. “The more warming we get (a sure bet if nothing is done to curb greenhouse gas emissions), the less water will be flowing in our rivers. Also, the less groundwater recharge we will get. Thus, the burning of fossil fuels threatens our sustainable water supply in a major way.”

A week after Overpeck spoke in Albuquerque, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released its latest temperature data for the United States.

According to the March data from NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information, 13 states were “much warmer than average” in March, with Colorado and New Mexico experiencing record warmth for the month.

The average U.S. temperature was 46.2 degrees Fahrenheit—4.7 degrees above the 20th century average. Meanwhile, in New Mexico, March was 7.9 degrees warmer than normal.

During his talk, Overpeck insisted that the news isn’t all bad. Southwestern states like California, Arizona and New Mexico can also focus on new opportunities with long-term economic benefits. “If we choose to get serious about resilience and adaptation, we can solve our water problems, and we can also solve our air quality problems and ecosystem problems,” he said, noting that those problems can only be solved by taking climate change seriously.

As the rest of the world warms, and people grapple with the problems the Southwest is already facing, states like California, Arizona and New Mexico can become net exporters of water and energy solutions, he said.

“That would be a sustainable economic engine, not a commodity that goes up and down,” Overpeck said. “It would be robust because everyone else in the world will want to be using it.”

Correction: The story originally read that the suit alleges that the federal government violated the young people’s constitutional rights to life, liberty and property by failing to act to prevent climate change. Our Children’s Trust wrote to clarify that the suit is focused not on the government’s inaction, but instead on the “affirmative actions that the U.S. government has taken and continues to take that cause fossil fuel production and greenhouse gas emissions.”