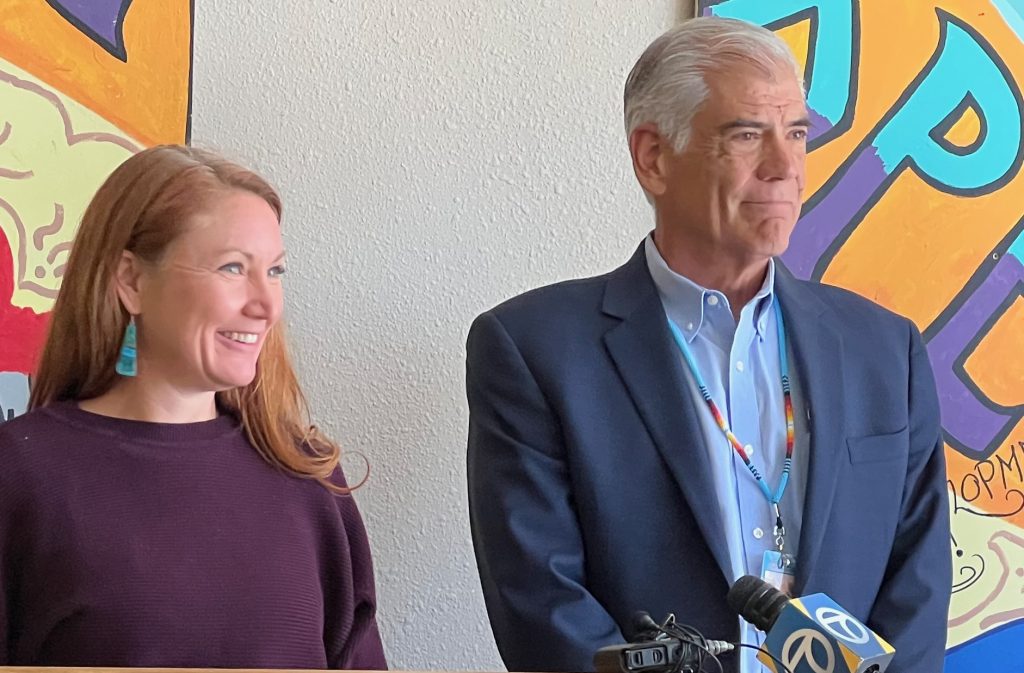

As he stood looking at an orphaned well in Kirtland, U.S. Secretary of Labor Martin Walsh asked, “is this ground dirty here?”

Activist Don Schreiber said yes and Adrienne Sandoval, the Oil Conservation Division Director for the state’s Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department, confirmed that there was surface contamination in places at the site. Sandoval said the contaminated soil will have to be removed from the site and clean soil will be brought in to replace it.

Walsh visited the orphaned well with U.S. Rep. Teresa Leger Fernández, a New Mexico Democrat who has been pushing for increased funding to assist states with cleaning up orphaned wells. They, and Aztec Mayor Victor Snover, met with Schreiber and Sandoval at the private property where the well is located.

Related: Federal lawmakers seek funds to plug orphaned oil and gas wells

The site is one of the hundreds of oil and gas wells in New Mexico that has no operator or responsible party to clean it up.

Walsh’s visit came just weeks after the U.S. Senate passed a bipartisan infrastructure bill that includes $4.7 billion in funding for the remediation of orphaned wells. This infrastructure bill is now waiting for the U.S. House of Representatives to approve it.

He said the $4.7 billion should make a good dent in capping the orphaned wells.

“The infrastructure package and the funding would provide the state with a really great opportunity to do more plugging work,” Sandoval said.

That means removing all the equipment on site and isolating the oil and gas producing zones using cement plugs, she said. Sandoval said the groundwater zones will also be isolated so that there is “no migration of any oil or gas into the water zones and there’s no migration of oil or gas also up into the air from the wellhead.”

In addition to protecting water and air, Sandoval said this process also protects existing oil or gas reservoirs for future production.

Related: Officials say plugging orphaned wells protects public health and environment

“We can’t describe it as anything other than a mess,” Leger Fernández said about the orphaned well. “But it’s a mess that is on a daily basis harming our environment. It’s not producing anything good for anybody.”

Orphaned wells can leak methane into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change. And they can also lead to groundwater contamination.

While oil and gas companies are responsible for plugging wells once production ends and remediating the landscape, this does not always happen. When companies go bankrupt, this can lead to orphaned wells. Companies are required to put up bonds before production to provide funding for clean up in the case of bankruptcy, but Leger Fernández said the required bonding levels are inadequate.

Related: House Natural Resources Committee passes bill addressing orphaned oil and gas wells

Leger Fernández has also introduced the Orphaned Well Clean Up and Jobs Act, which, if passed, would provide $7.25 billion in funding for clean up and plugging of orphaned wells on state and private lands and includes $700 million in funding for remediation on tribal and public lands. This bill would also increase the bonding levels required for oil and gas operators.

A study released earlier this year found that there is a $8.1 billion gap between the bonding level for the thousands of operating oil and gas wells in the state and the amount that it will cost to clean up and remediate each of those sites.

Related: Analysis finds $8.1 billion gap in New Mexico bonding requirements, clean up costs for oil and gas

Leger Fernández said the bonding levels were set in the 1950s and that the cost of doing business now is not the same as it was back then.

In addition to sponsoring efforts to increase funding for plugging and clean up of orphaned wells, Leger Fernández has pushed for increased bonding levels.

And cleaning up these wells will create hundreds of jobs for New Mexicans.

As they looked at the well and the pump jack, Leger Fernández told Walsh that these will be high-paying jobs in disadvantaged communities, including Indigenous communities, that have been impacted by pollution from oil and gas production.

The OCD contracts with local, New Mexico companies to perform the work, Sandoval said.

“You can create dozens of jobs just at one site,” Sandoval said. “And then if we have the funding to do site after site after site, what that really allows those companies to do is to sort of staff up. If they know they’re going to have funding for the next year or two years, they can hire more people and really create long-term jobs.”