Anyone who recently watched recent floodwaters rip down the Santa Fe River or the Rio Puerco—or had a skylight punctured by hail—might be tempted to declare that the annual monsoons ended New Mexico’s drought.

But breaking the drought requires more than a handful of rainstorms—even big storms. And grappling with its impacts means policymakers should listen to scientists and constituents, ranging from farmers to city-dwellers.

“Even though we got a lot of rain, and there’s great reporting on floods and great pictures on the internet, it’s a slow process to make up for what we’ve lost,” said New Mexico’s State Climatologist, David DuBois.

The weekly New Mexico Drought Monitor, released Thursday, shows improvements in New Mexico, mainly in the eastern part of the state. But 99.9 percent of the state is still in drought, with 46 percent of the state experiencing exceptional or extreme drought conditions. Compare that with this time last year, when 95 percent of the state wasn’t experiencing any drought conditions.

[aesop_image img=”https://nmpoliticalreport.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/20180731_NM_trd.png” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Even if storms continue dumping rains in certain parts of the state, it will still take another month of steady storms to improve conditions, said DuBois. That’s because the current drought episode began last fall. And the winter’s “snow drought” continues to hurt New Mexico’s water supplies.

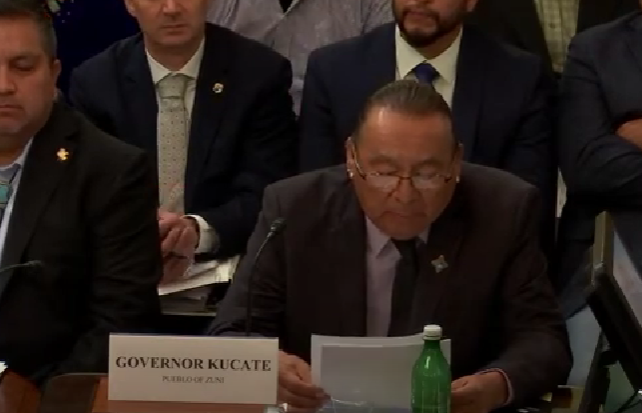

Navajo Reservoir on the San Juan River, has dropped about 100,000 acre feet since last month. On the Pecos, water managers released 30,000 acre feet from Santa Rosa Lake to Brantley Reservoir downstream for the Carlsbad Irrigation District. Heron Lake on the Chama River is down about 30,000 acre feet from last month—and nearby El Vado Reservoir is holding only 9,000 acre feet in total right now. Irrigation water is also being released from Elephant Butte Reservoir, which is at 6.4 percent capacity.

The Middle Rio Grande is flowing continuously for the first time since April—thanks to storm flows through the Rio Puerco and Albuquerque’s diversion system—but its levels are still low. So are the Jemez River, the Animas River and the Pecos River.

[aesop_image img=”https://nmpoliticalreport.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/IMG_1930.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” caption=”Abiquiu Reservoir on the Chama River at the end of July” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Even if winter precipitation looks good on paper, if it falls as rain instead of snow, that’s a problem for New Mexico. “Then you have the rain soaking in, and we’re not getting the storage we need for later when we have the runoff season,” DuBois said. “Even if we have good precipitation, it bites us in the tail because we don’t get that delivery when we need it in the spring.”

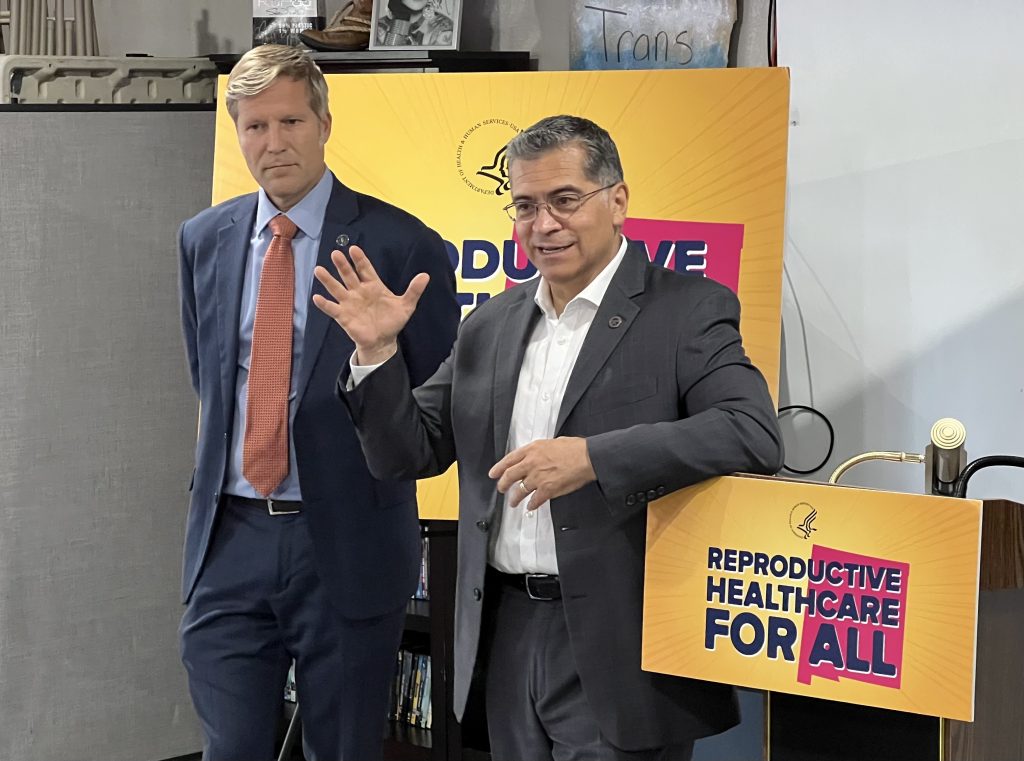

Better communication

DuBois regularly travels the state, holding workshops, visiting with farmers and ranchers and maintaining monitoring sites. He said most people he meets, from all walks of life, understand the climate is changing and the region is warming. But they don’t know what to do.

Scientists can provide outlooks and projections. But people are unsure what to do with that information. “There needs to be more discussion of problem-solving,” he said. There also needs to be better communication between scientists and policymakers.

Scientists sounded the alarm last fall about drought conditions. By January, with a lack of snowpack in the mountains, the situation looked dire—and by spring, exceptional drought conditions had taken over the state.

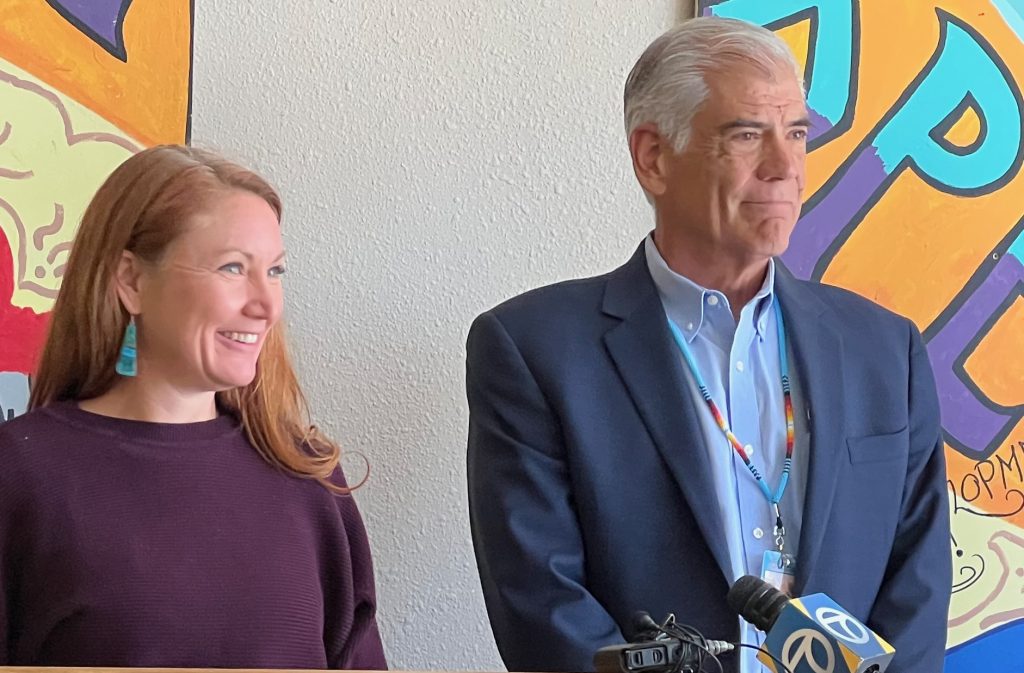

Yet, the Office of the Governor failed to issue a drought declaration until July, when 98.6 percent of the state was already rated abnormally dry or worse. From San Juan County to Union County, crop reports showed that range conditions were poor and water availability low. Not only that, but aside from issuing the July 11 executive order, Gov. Susana Martinez does not appear to have taken any action on the emergency.

[aesop_image img=”https://nmpoliticalreport.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/IMG_0100-1.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” caption=”By early April, the state’s largest river, the Rio Grande, had already dried south of Albuquerque” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

According to the order, the state has suffered a prolonged drought since October 2017, raising the risk of wildfire, agricultural losses and flooding due to severe wildfires. It also acknowledged that drought is threatening drinking water and irrigation supplies—and it might take several years of higher than normal levels of snowpack and precipitation for reservoirs and soil moisture conditions to recover.

The drought is of such a magnitude, according to the order, that it is beyond local control and requires additional resources. Not only that, but “extraordinary measures may be necessary to protect public health, ensure public safety and wellbeing, and provide for the economic stability of the state.”

As part of the statewide emergency, Martinez ordered the State Drought Task Force to review and recommend actions, as well as recipients of emergency funding, to the governor.

But the governor has yet to convene the Drought Task Force, and drought planning links on the governor’s website show only a 2006 New Mexico Drought Plan and 2008 recommendations from the task force. Both those documents precede Martinez’s tenure as governor.

NM Political Report called and emailed Benjamin Cloutier, the Office of the Governor’s communications director. Cloutier did not respond.

‘Cautiously optimistic’ about El Niño

The monsoon rains have been good for many places across the state, but Royce Fontenot, senior service hydrologist and incident meteorologist for the National Weather Service in Albuquerque, likes to use the human body as an analogy.

“Your body expects food and nourishment at certain times, and when you don’t get that, it suffers,” he explained: “Say someone handed you a Big Mac”—a heavy monsoon storm—“that might help you for a day or two, but you’re still starving.”

It’s the same with the ecosystem: Even a few heavy rainstorms aren’t enough to make up for the lack of precipitation over months and months.

New Mexico is an arid state, he said, but that doesn’t mean drought isn’t a problem.

“By and large, New Mexico is a dry state—we do go from White Sands to beautiful high-elevation forests—but the ecosystem expects water, even if it’s not a lot of water,” said Fontenot.

[aesop_image img=”https://nmpoliticalreport.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/IMG_2168-m.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” caption=”The Valle Grande still has a ways to go toward greening up ” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Mountain ecosystems are dependent upon snows, as are the state’s two biggest rivers, the Rio Grande and the Pecos River. “Even in the desert, we have precipitation at certain times of year, and the system expects that,” he said. “When we don’t have that, and don’t have that over time, the deficits build.”

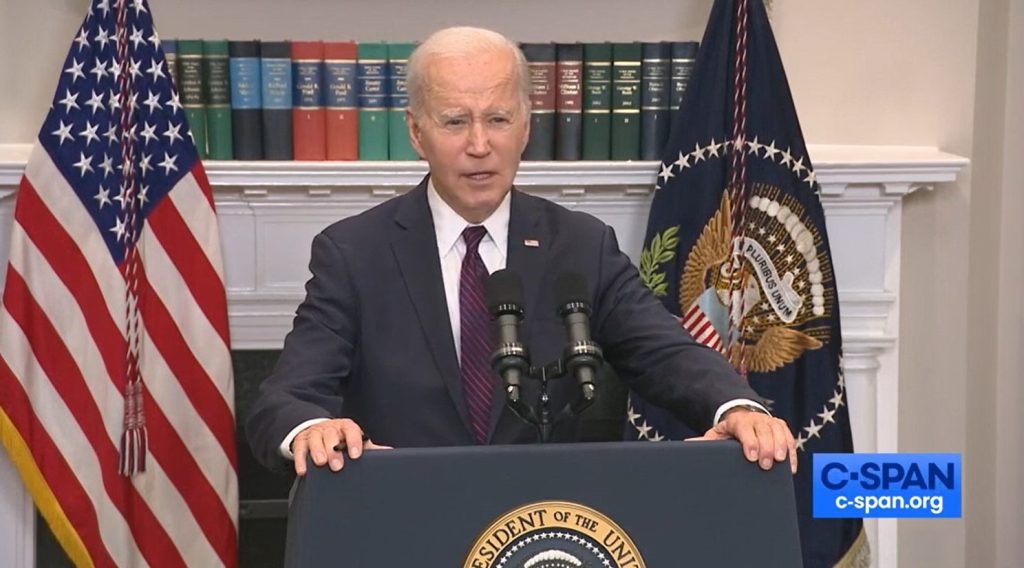

There is some good news: El Niño is (probably) coming.

Currently, there’s a 75 percent chance of El Niño conditions in the northern hemisphere this winter.

El Niño is dependent on sea surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific Ocean—and for New Mexico, El Niño conditions can mean increased precipitation: better monsoons in the summer and increased snowfall in the winter.

Right now, the three-month outlook for August through October shows robust monsoon conditions, which will improve drought conditions, but probably not eliminate them altogether. Into the fall and early winter, forecasts indicate El Niño could bring normal and above-normal precipitation for the state.

Fontenot is cautiously optimistic about El Niño. The catch, he said, is how much precipitation will New Mexico and its watersheds receive—and in what form. El Niño sets up a good chance for cooler and wetter conditions over the winter, but it’s a system that can shut down.

“The $64,000 question then is, What if we don’t have a normal winter? What if we have a bust winter?” he asked. “What if we don’t have a good water year?”

This year’s reservoirs are only as high as they are due to water stored from past good years. If New Mexico misses out on another snowpack, many of the state’s reservoirs will be nearing empty.

New Mexico experienced record high snowpacks during the winter of 2016-2017—and then record lows in 2017-2018, Fontenot pointed out. “How do you plan for one year, where you’re worried about flooding, and then six months later, you’re worried about having enough water to keep your community alive?” he asked: “You need to be planning for variability.”

[aesop_image img=”https://nmpoliticalreport.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/NASA-June-2018.png” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Climate change is “changing the baseline,” he said. And in New Mexico, that means changing what we expect in terms of water.

On Wednesday, NASA announced that June 2018 tied for the third-warmest June on record, continuing a four-decade long warming trend. The agency’s monthly analysis is based on 6,300 meteorological stations worldwide, sea surface temperature readings and research stations in Antarctica. And the National Weather Service noted yesterday Albuquerque is on pace for its warmest year on record.

In all sectors—from agricultural to urban—people should be planning for variability, said Fontenot—figuring out how to take care of this year’s boom, and this year’s bust.